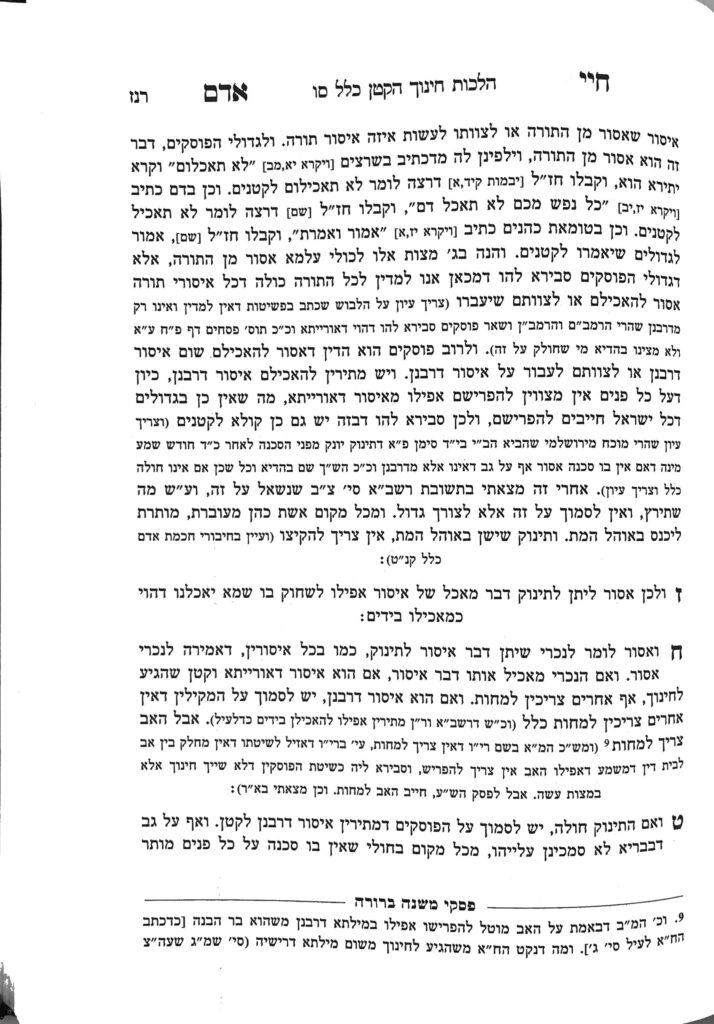

We are continuing in siman 6, regarding sefiya b’yadayim on Shabbos. We learned that both according to the Imrei Binah and the Achiezer, it is assur to perform sefiya b’yadayim on a child, even though the action they are performing is lacking in meleches machsheves (and even though the Imrei Binah and Achiezer assur for different reasons).

There is one exception, which is a case of a psik reisha. The example we gave yesterday, of toggling a light switch, is a prohibited action on shabbos due to the direct consequence of the action. By a psik reisha, the action itself is permitted, but it causes another result which is assur. Generally, an unintended result from an action is called a davar she’eino miskavein and is muttar. However, by a psik reisha, since it is inevitable that the assur action will result, the entire action is considered a davar hamiskavein and is assur. One example would be to open a refrigerator door when one knows they will turn on the light. Although the action of opening a door is muttar, since it will inevitably lead to an assur result, the entire action is assur.

The Achronim discuss the sevara behind the issur of a psik reisha. One opinion is that since the assur action is inevitable, it is as if the person is being mechavein for the assur action when they do the muttar action. This sevara would not apply to a child, because a child (of the appropriate age) has no awareness of the resulting consequences of their actions.

The example of the refrigerator is different than the example of the lightswitch, because the action is intrinsically muttar, just the presumed added kavanah for the second action makes both actions assur. However, for a child who does not have that presumed added kavanah, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach writes that the issur does not apply. Thus, it is muttar perform sefiya b’yadayim to enable a child to perform a psik reisha even on an issur d’oraysa. Although there is another explanation behind the issur of psik reisha, which would apply to a child, Rav Shlomo Zalman appears to accept the above explanation as the primary explanation.

The Chayei Adam moves on to discuss a scenario related to tumas kohanim. One may have thought that a pregnant woman who is married to a kohen should need to suspect that the fetus is a male, and should treat the fetus accordingly. There is an issur for a kohen to be metamei himself, so we should argue that the mother should need to protect herself from coming in contact with tumas meis. However, the Chayei Adam writes that it is muttar, because there is a heter of a sfeik sfeika: a safeik whether the fetus is a boy, and, even if it is a boy, a safeik whether the fetus will be viable. Thus, the rov tells us that we do not need to be concerned. However, it is important to note that the rov does not apply if the mother knows the gender of the child, because there is no longer a sfeik sfeika. In such a case, the mother is prohibited from coming in contact with tumas meis.

We would appear to conclude from this halacha that a fetus can have a separate status than its mother, and, since we consider the fetus to be a kohen, the issur of sefiya b’yadayim (i.e., to actively bring the fetus to a tamei place) applies. However, the question is raised whether we would look at the child as distinct from the mother, or whether the tumah of the mother cannot extend to her child. We have a concept of taharah beluah, that something completely absorbed in the body is considered tahor. The examples discussed in the Mishnayos regard an animal which consumes an item whole and then releases it whole via its waste.

There is a machlokes achronim whether the concept of tahara beluah applies to a mother and fetus as well. The achronim who hold that tahara beluah applies to a mother would argue that this concept could be used to allow the mother to come in contact with tumas meis, even without the sfeik sfeika, due to the inherent nature of the child being fully absorbed within the mother..

Thus, a mother could go to the hospital, even though there may be a meis there, relying on either the sfeik sfeika or the concept of tahra beluah. Nevertheless, due to the sfeikos, if she has no pressing need to go to the hospital, she should avoid doing so.

Summary

- The Chayei Adam understands that sefiya b’yadayim to a katan on anything assur mideoraysa, or to tell a child to do any action which is assur mideoraysa, is an issur deoraysa.

- Sefiya b’yadayim on anything assur miderabanan is assur as well, but there is an opinion one may rely on (the Rashba) under compelling circumstances to perform sefiya b’yadayim. Either way, it may only be relied upon for the child’s benefit, not for a child to benefit an adult.

- All agree that one may perform sefiya b’yadayim even on an issur deoraysa in a case of a psik reisha.

- A pregnant woman married to a kohen may enter a place with a possible tumas meis (e.g., a hospital) if necessary. If it is not necessary, she should try to avoid it.