The current series, which will cover seudos Shabbos and fasting on Shabbos, is available for sponsorship. Please contact Rabbi Reingold for more information.

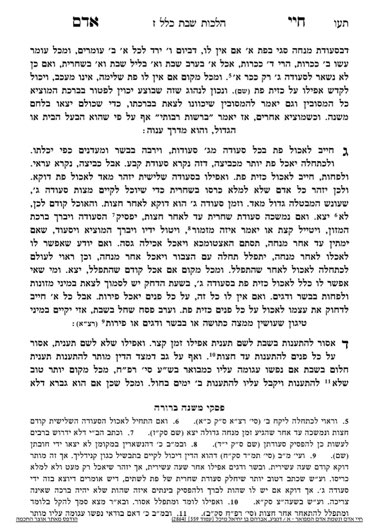

We are continuing in siman 4, discussing fasting on Shabbos. We learned that the Chayei Adam writes that a person who is not affected or scared by their bad dream is not allowed to fast on Shabbos. The whole leniency to fast on Shabbos is that it is the person’s oneg Shabbos, because it makes them feel better. If they will not feel any better, they have no permission to fast. Similarly, even if a person is scared by their dream, if fasting will make them feel horrible, they are not allowed to fast either, because the benefit is outweighed by the disadvantage. In truth, they should not fast during the week either, and should use one of the other options we discussed.

A person who does fast will recite aneinu in the mincha shemoneh esrei. Sephardim say it in shachris as well. The question comes up whether the tefilah should be said in the plural form, as we normally say it (“tzom ta’aniseinu”) or singular form (“tzom ta’anisi”). The poskim conclude it should be recited in plural because one can assume there is another Jew, somewhere in the world, who is fasting as well.

When a person is fasting a private fast, there is a special tefillah inserted at the end of shemoneh esrei, in elokai netzor. It is recited on Shabbos as well.

We learned that it is a machlokes whether fasting on Shabbos is an issur deoraysa or issur derabanan. The Chayei Adam assumes it is deoraysa, but the Piskei Mishnah Berurah points out that the Biur Halacha brings differing opinions. The Biur Halacha points out that everyone agrees that the issur to fast for part of the day is certainly derabanan.

The Chayei Adam writes that the source for the issur deroaysa is either the pasuk ichluhu hayom, as we have learned, or mikra kodesh. Rashi explains that this second pasuk teaches us Shabbos and Yom Tov should be special days and declared as such through food and drink (besides for Yom Kippur, where it is declared through special clothes). On the flip side, when a person eats on Shabbos, they are fulfilling all of these concepts.

The Telsher Rov discusses the importance of a taanis chalom, and why we give it significance if it is “just” a dream. He explains that Hashem formulates various decrees in shamayim, and finds ways to filter them down into this world. We do not see the decrees; we only see the final results. When a person is sleeping, the neshama is freed somewhat from the confines of the body, and is able to see the existence of this decree in the spiritual realms before it has been concretized into something physical. Thus, a dream can be the neshama seeing something before we are able to tangibly concretize it in our world, and that is why we attach significance to it. Chazal tell us that there are dreams which are a result of things a person saw or thought about during that day, and there can also be parts to a “real” dream which are a result of a person’s imagination and not part of what they are seeing in shamayim, but we have a better understanding of why we attach such significance to a dream.

Summary

- If a person will not feel better by fasting, either because they are not concerned by their dream or because fasting will be uncomfortable for them, they cannot fast on Shabbos.

- A person fasting recites aneinu and the special tefillah at the end of shemoneh esrei.

- The significance of a dream is that it may be the neshama perceiving a decree in shamayim.