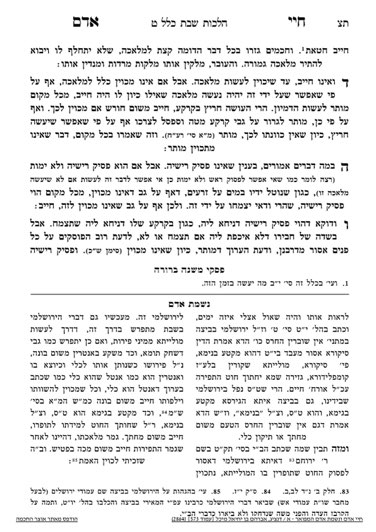

We are continuing in siman 5, and we left off discussing a Rema in Yoreh Deah, where the Rema is discussing a case of pots cooking above the hearth. Although the case does not seem to be a psik reisha, the Rema holds it is assur, even though it should only be a davar she’eino miskavein.

Rav Akiva Eiger answers our question. He explains that if we think fundamentally about davar she’eino miskavein, we should be machmir on every case of davar she’eino miskavein due to the concept of safeik deoraysa lechumra. He answers that we only apply the concept of safeik deoraysa lechumra when a reality already exists, but it is not known to the person whether it is assur or not. Davar she’eino miskavein refers to where a person is performing a specific action which may, in turn, cause another action as a result of the first action, but at the time of the performance of the first action, the second action is not in existence and unknown. Thus, the assur action is a separate action from the muttar action. Therefore, it is different from the case of the pots, where the reality already exists. The language of the poskim is safeik l’she’avar, where the safeik is a question of the reality on the ground, or a safeik lehabah, where the current action may later cause a second step.

An example of the difference between these two types of safeik is a case of a person who wishes to open a refrigerator door on Shabbos and cannot remember whether they turned off the lightbulb. (If the bulb has a filament inside, it may be a safeik deoraysa.) In such a case, the safeik is l’she’avar, because the reality is clear, just the person/people asking do not have the information. Thus, davar she’eino miskavein only refers to scenarios where what is being done may generate results, but because the two actions are looked at as a two-step process, as long as one does not have kavanah for the second step of the process, the second step will be muttar. Nevertheless, if it is a psik reisha, it will be assur because of the continuous connection between the two actions. If the reality exists already, just that it is unknown, as in the refrigerator case, the heter of davar she’eino miskavein does not apply.

There is a Taz which disagrees, and holds that even a case of safeik l’she’avar is called davar she’eino miskavein and will be muttar. The Biur Halacha suggests that when dealing with an issur deoraysa, one must treat it as a safeik deoraysa lechumra and not follow the Taz. If it is a safeik derabanan, there is much more room to be lenient.

Really, every scenario can be understood as being a result of an antecedent, and should be a safeil l’she’avar. just that it may require further scientific evidence to determine its direct correlation. Thus, for example, when dragging a bench, the speed, force, external focus and pointiness will all help determine what the result is. If we knew all of that information, the result would be automatic, so the reality is here already, just unknown to us. However, as far as it relates to our question, since it is still a result of the first action, it is called causative and is not taken into account.

Summary

- Davar she’eino miskavein is the general Torah concept of performing one action with an unintended aveirah which may occur in addition. We pasken in accordance with Rav Shimon, that it is muttar

- However, if it is inevitable that the unintended aveirah will occur, it is called a psik reisha that the unintended action will occur, and one becomes chayav mideoraysa for causing that unintended assur action to occur.

- If it is karov l’psik reisha, many consider it a psik reisha; however, Rabbi Reingold’s mesorah is not to treat it as psik reisha but rather as a davar she’eino miskavein.

- A safeik l’she’avar is treated like a psik reisha when the safeik is a safeik deoraysa. When the safeik is a safeik derabanan, some are meikil to treat it like a davar she’eino miskavein.