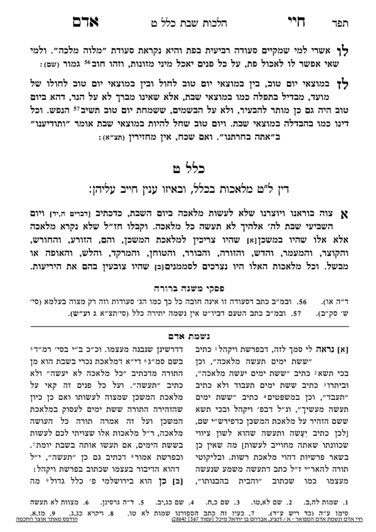

We are continuing in siman 1, where the Chayei Adam is giving a brief introduction to the melachos. We left off with some pairs of melachos. The Chayei Adam discussed koseiv and mocheik, boneh and sosair, and mechabeh and mavir. We will go over these pairings and add some points.

Regarding boneh and sosair, the Chayei Adam points out that binyan l’shaah, binyan for a short amount of time, is considered boneh. He brings a proof from the mishkan, where sometimes the mishkan remained in a place for a short amount of time.

The Yerushalmi discusses this question, and points out that generally we have a concept of meleches machsheves, which includes the requirement that the melacha remain (davar hamiskayeim) in order for it to be chayav. Thus, for example, writing which will not remain is not chayav (mideoraysa). However, we see from the mishkan that the act of boneh is so significant that it is considered boneh even when it is for a short amount of time. Therefore, one will be chayav.

We will learn that one of the requirements for an act of melacha to be chayav is that it be a constructive act, not mekalkeil (a destructive act). Therefore, mocheik is only chayav if it is al menas lichtov, for the purpose of writing afterwards. The same would apply to sosair, in that it will not be chayav unless it is for the purpose of building afterwards. Destroying something purely for the purpose of destruction is not chayav (mideoraysa).

In giving examples of destructive melachos which are chayav (i.e., where the destructive act is for constructive purposes), the Gemara gives the examples of destroying the mishkan to rebuild it elsewhere and tearing a garment to resew it. If a person does not plan to perform another melacha, but the destructive melacha is in and of itself beneficial, it is also chayav. For example, if a person has a garment where the opening for the head is sewn shut, if a person tears the threads to open the head, they would be chayav.

Similarly, regarding mechabeh and mavir, the destructive act of mechabeh will only be chayav mideoraysa if it is for a constructive purpose afterwards.

The Chayei Adam writes that the melacha of makeh bepatish is the concept of the final act performed on an item in order to complete it. Even if there was no other melacha involved in that final act, the fact the object was completed has inherent importance, and is assur in and of itself under this melacha of makeh bepatish.

The Chayei Adam writes that the actual case of makeh bepatish in the mishkan was when they would bang down strips of gold until they were thin enough to be cut and woven into the bigdei kehuna. That process would require occasionally flattening the head of the hammer or anvil so that it would not tear the thin metal being processed. Thus, it was not part of the creation of the item (hammer or anvil) itself, but something done as part of its usage.

Alternatively, some understand it is the final blow on the gold itself which makes it ready for use.

The last melacha is the hotzaah, carrying, from one domain to another. The Gemara brings pesukim to support the concept of the issur. Tosfos explains that the Gemara brings pesukim to support this melacha because nothing inherently changes in the item, so the fact it is assur is considered a melacha garu’ah, a minimal melacha, and therefore we need pesukim to teach us it is still chayav. Rav Hirsch discusses this melacha in his sefer Choreiv; those who are interested should take a look there.

Summary

- Binyan l’shaah is not considered boneh.

- Melacha is only chayav mideoraysa if it is for a constructive act.

- Makeh bepatish is the melacha of the final act performed on an item in order to complete it.

- Hotzaah is the melacha of carrying from one domain to another.